When everything is viewed as a commodity or up for sale then decisions are merely a matter of financial capability and desire. As such, markets not only assign financial values to everything, therefore rendering them meaningless, they also lead to inequality and distance between the wealthy and the poor. Sandel uses sports stadiums as a great example of this where the rich now separate themselves from the rest in their luxury skyboxes:

“Skyboxes, for all their cozy frivolity,” wrote Jonathan Cohn, “speak to an essential flaw in American social life: the elite’s eagerness, even desperation, to separate itself from the rest of the crowd … Professional sports, once an antidote to status anxiety, have been stricken grievously by the disease.” Frank Deford, a writer for Newsweek, observed that the most magical element of popular sport was always its “essential democracy …

The arena made for a grand public convocation, a 20th-century village green where we could all come together in common excitement.” But the luxury boxes of recent vintage have “so insulated the swells from hoi polloi that it is fair to say that the American sports palace has come to boast the most stratified seating arrangement in entertainment.” A Texas newspaper called skyboxes “the sporting equivalent of gated communities,” which enable wealthy occupants “to segregate themselves from the rest of the public.”

I have previously discussed in my previous posts about how consumption-based happiness seeking can leave us lonely and never truly happy. Though this book does not discuss psychological impacts of consumerism and market-based thinking on individuals, it does emphasize the dangers of such a system and way of thinking if it infiltrates every corner of our lives:

Addition to debating the meaning of this or that good, we also need to ask a bigger question, about the kind of society in which we wish to live. As naming rights and municipal marketing appropriate the common world, they diminish its public character. Beyond the damage it does to particular goods, commercialism erodes commonality. The more things money can buy, the fewer the occasions when people from different walks of life encounter one another. We see this when we go to a baseball game and gaze up at the skyboxes, or down from them, as the case may be.

The disappearance of the class-mixing experience once found at the ballpark represents a loss not only for those looking up but also for those looking down. Something similar has been happening throughout our society. At a time of rising inequality, the marketization of everything means that people of affluence and people of modest means lead increasingly separate lives. We live and work and shop and play in different places. Our children go to different schools.

You might call it the skyboxification of American life. It’s not good for democracy, nor is it a satisfying way to live. Democracy does not require perfect equality, but it does require that citizens share in a common life. What matters is that people of different backgrounds and social positions encounter one another, and bump up against one another, in the course of everyday life. For this is how we learn to negotiate and abide our differences, and how we come to care for the common good. And so, in the end, the question of markets is really a question about how we want to live together. Do we want a society where everything is up for sale? Or are there certain moral and civic goods that markets do not honor and money cannot buy?

-Sandel, Michael J. (2012-04-24). What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of MarketsAdditionally, comparing salaries of bankers, management consultants with chefs, engineers and carpenters is another example that markets don't necessarily allocate financial rewards based on hardwork, smarts or benefits to society but only market demand. However, demand itself has no moral or ethical rules or reason, prostitution being one example. If people demand it markets will provide it, price it and sell it. Markets are very efficient but with no moral or ethical codes or rules. The sad part is that market-thinking makes people judge themselves based on their financial status which often has nothing to do with how smart or creative they are, but rather how well they can work in a demanding fields. For example, if markets rewarded people based on smarts and hard work NASA scientists putting a robot on Mars would make more money than MTV reality stars but not the case not even close.

The irony remains that more money actually leads to less satisfaction, more status anxiety and more social isolation (country clubs, gated communities, infinite consumption and material belongings) and more meaningful and stimulating professions such as engineering, cooking, design and art are satisfying and engaging activities themselves regardless of financial incentives. This is where markets fail to consider the human factor, instead they assume people are robots and money is their fuel. People are humans with emotions, joys, hopes and fears and feed on social connections, respect and engaging hobbies and activities, things that can not be reduced to financial transaction or commodities.

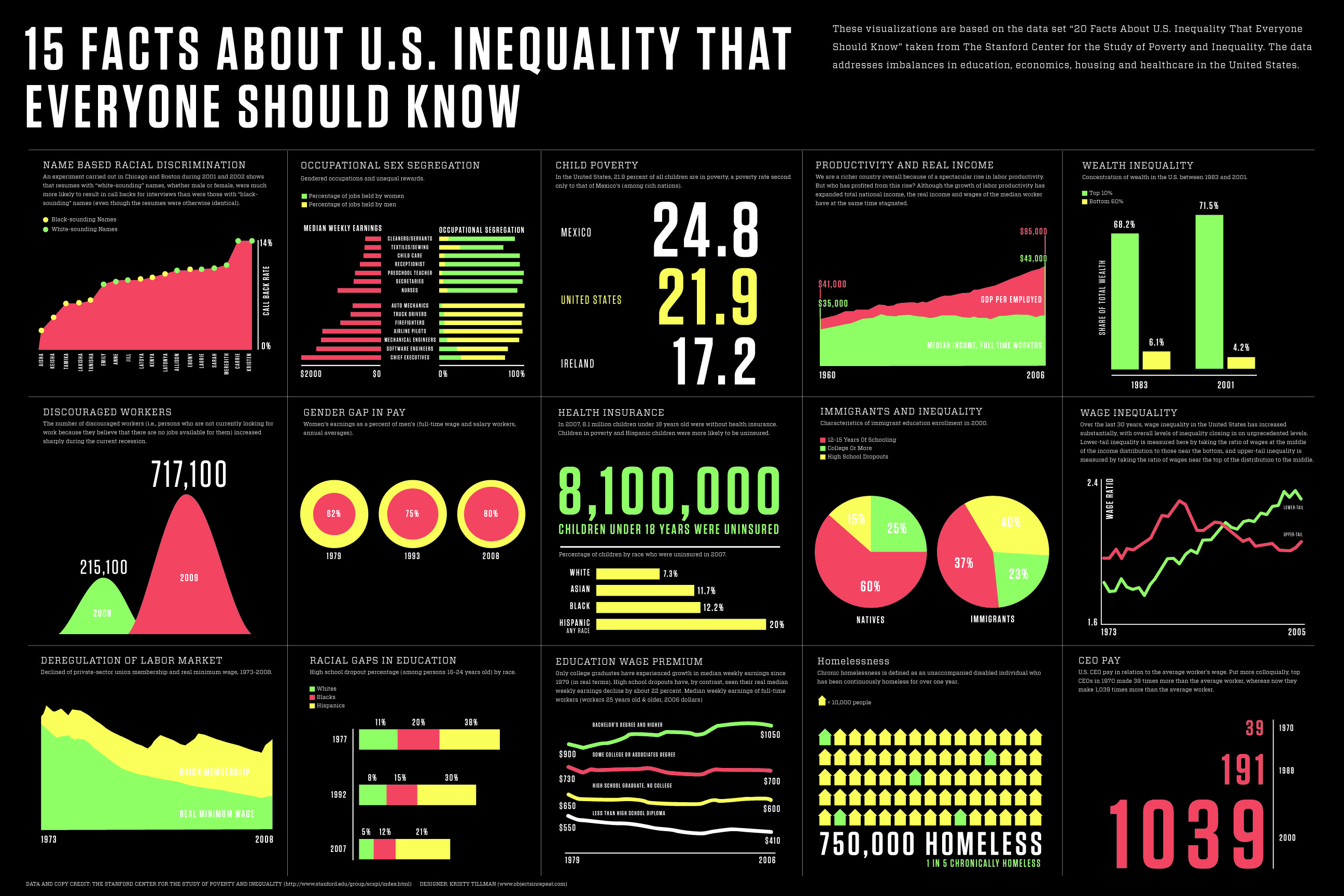

Click to view the full sized version. This infographic originally appeared in an article titled: Infographic of the Day: 15 Facts About America’s Income Inequality on FastCompany.

No comments:

Post a Comment